… where top level sport and business collided!

An intellectual property perspective

I don’t mind a sail. Sailing has stuck with me since I first was introduced to the Optimist dinghy in my home town’s public swimming pool when I was about 4 or 5 years old.

I moved through the various dinghies in the NZ development pathway, concluding with the ‘Laser’ dinghy. This class of boat has been my core competitive outlet ever since.

As a sailing instructor and coach, I believe this boat has so much to offer anyone looking to either learn to sail or advance their knowledge/skills in sailing. We use these boats as a sail training dinghy at our local club, as they continually prove to be fantastic platforms for learning the sailing fundamentals safely efficiently, and competently.

All this, in my view, derives from the visionary design from its creator – Canadian Bruce Kirby.

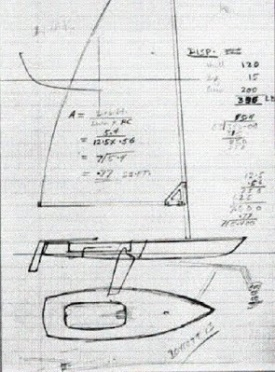

Like all great ideas, the laser dinghy originated from a paper doodle (shown below).

The initial concept was for the boat to be car topped, enabling quick transport to the beach, but be fun/fast on the water.

The boat hit the world stage in late 1970 as the ‘Laser’, and was a hit – becoming an internationally recognised sailboat class in 1974. To date, more than 220,000 boats have been built with fleets racing in around 141 countries – and at the Olympics.

The ‘Laser’ dinghy has become internationally renowned for its robust construction, simple rig and ease of sailing, and the close competitive nature of racing which is due to the tight manufacturing control which reduces or eliminates differences in hull, sails, and related equipment. The ‘Laser’ dinghy is what is rereferred to as a ‘one-design’ class of sailboat – where all boats are manufactured to tight tolerances so that rewards and losses in racing result more from sailor skill, and less from differences in equipment.

A number of different rigs (suited to sailors of different weight groups) were also developed for use with the ‘Laser’ dinghy hull.

The ‘Laser’ dinghy using the original ‘standard’ rig (now ILCA 7) was introduced as the single handed mens dinghy equipment for Olympic Games competition in 1996. Using a smaller sized ‘radial’ rig (now ILCA 6), the ‘Laser’ dinghy has been the single handed womens dinghy equipment since 2008.

These are fantastic achievements for Bruce Kirby’s creation. He has been responsible for shaping many lives around the world with his visionary design.

Lets get into it

But like all great things, the story of the ‘Laser’ dinghy is not without its own flavour of controversy.

The days of the ‘Laser’ designator are (sadly, I think) now in decline in favour of the adoption of a new badge, the ‘ILCA Dinghy’. This new designator is an acronym for the International Laser Class Association (ILCA), which is a ‘self-administered, self-funded’ international body that ‘provides coordination, organization, and communication for the class worldwide’. As stated on its web page, ‘ILCA is like a worldwide sailing club specifically for owners of ILCA sailboats and people interested in sailing them’.

There is a good reason for this change, as I will try to outline below

But, before we start …

This outline is not intended as a detailed documentary fit for use as a future authority on the matter. Its purpose is for interest and to glean some learnings as regards commercial and intellectual property practice that might be of use to emerging innovators, like Kirby was in 1970, moving forward in releasing their creations on the world.

What I am attempting to piece together is very complex. Various litigations have taken place in the United States and Europe that have played a part in where things have converged to now. My understanding of the history cannot be complete, and derives only from publicly sourced information, mainly court judgements and various commentaries where I have been able to find comfort with the accuracy of the reports.

It is simply not possible to review everything that has been reported on this history in a reasonable time frame, and in a digestible form for readers. I have sought to distil what has appeared from my research to be the main aspects of relevance to the history of the class and the related intellectual property issues in a readable manner, and welcome suggestion for improvement.

The setup …

As noted above, the ‘Laser’ dinghy became known to the world in late 1970. Kirby also took the step of forming an incorporated a company, Bruce Kirby Incorporated (BKI), for his boat designs.

Kirby wasn’t a boat builder, but a friend of his (and early collaborator on the project), Ian Bruce, agreed to manufacture the boat with Kirby receiving royalties on each build.

As the story goes, the name ‘Laser’, and the associated sail insignia (the “starburst” sign), was suggested by one of Kirby’s young sailing friends, Doug Balfour, a then university engineering student who noted that lasers were well known to young people (of the time), and internationally known.

I’m sure Kirby would not have appreciated, at that time, the impact that this name/brand would ultimately have in the global market in the coming years, nor the resilience of its distinctive character as a trade mark registration when tested during litigation 40 odd years later.

Addressing global demand …

Demand for the ‘Laser’ dinghy grew.

In the early days, a single manufacturer, Performance Sailcraft International (PSI), was appointed. At this time, PSI held rights to the LASER trade mark and the starburst insignia in most parts of the world.

As international demand grew, it was realised that regional manufacturing would enable the global demand to be satisfied more economically than exporting the boats from Canada.

New builders were approved and granted a license to the confidential construction information (what became known as the Laser Construction Manual), as well as the rights to use the LASER trade mark in certain territories. Commercially, this exclusive approach had the effect of limiting competition for the production of class-legal equipment and made the rights to build and sell the boat more lucrative.

In the early 1980s, PSI folded. This resulted in two significant outcomes for the ‘Laser’ class: firstly, the confidential construction information came under joint control of the established international class association (ILCA), Bruce Kirby and the licensed builders that existed at that time; and, secondly, each of the licensed builders were allowed to acquire ownership of the LASER trade mark in its territory.

Approaching 2020, the trade mark situation as regards the LASER mark and the associated starburst was as follows: Performance Sailcraft Japan owns the trade mark for Japan and Korea, Performance Sailcraft Australia owns the trade mark for Oceania, and Velum Limited (who licenses the trade mark to LaserPerformance) claims rights to the LASER trade mark in other parts of the world.

We will return to the trade mark situation later with regard to Velum Limited.

A brief comment on the territorial ownership of the ‘Laser’ brand

As yet, I have not been able to learn more as to why the licensed builders were allowed to acquire territorial ownership in the manner that occurred.

Without knowing the actual circumstances that led to that particular decision, I am limited in my ability to comment. Above all else in this story, it is that decision that I find most interesting as, to my mind on the information that I am aware, had ownership of the ‘Laser’ trade mark rights rested entirely with Kirby or BKI, then much of what I outline below should have been avoidable, or at least been addressed with much less complexity.

Introducing ILCA …

In 1974, sailors of the ‘Laser’ dinghy organised into an international class association (ILCA) which sought to codify the design into a very strictly defined set of specifications. This led to recognition as a distinct class of sailboat by sailing’s then international governing body (the International Sailing Federation, or ISAF), now known as ‘World Sailing’.

Also during 1974, ILCA and ISAF entered into an agreement which required that all ‘Laser’ dinghies built and raced be constructed using a single set of design and material specifications detailed in a build manual. This is, in effect, the bible of the construction of the boat, known as the ‘Laser Construction Manual’.

Since the early 1980s, Kirby and his company licensed various builders around the word the right to build ‘Laser’ dinghies under what we will call ‘Builder Agreements’.

Speaking to the general commercial history of the ‘Laser’ dinghy, ILCA provides the following on its website:

“Throughout the history of the class it has been the license agreements along with the trademark rights that have determined where builders can sell their equipment. This controlled market generally worked well during the earlier, high-growth era of the class with multiple builders on nearly every continent giving reasonable access to equipment. But over the past decade continued consolidation of builders has led to chronic supply issues in several parts of the world, with restricted territories preventing other builders from stepping in to help alleviate the problem. The result has been limited growth and restricted access to equipment in many areas of the world, leaving ILCA struggling to work within the existing structure to find solutions.”

The above could well be a fair assessment. And an unfortunate outcome for ILCA in trying to deal with competing commercial interests for the maintenance and continuance of the legacy of the ‘Laser’ class in an increasing commercial environment.

Again, the approach taken with the territorial assignment of the trade mark rights to various of the licensed builders of the time is, in my view, questionable – and a contributing factor to the problems that arose, or at least the difficulty in being able to resolve those problems without requiring litigation.

The builders …

Two builders involved heavily in this story acquired Builder Agreement rights with Kirby and BKI by having inherited these interests from prior holders: the first is LaserPerformance (Europe), or ‘LPE’, in 1983; and the second is Quarter Moon Incorporated, or ‘QMI’, in 1997. LPE is headquartered in the UK and was the dominant builder of the ‘Laser’ dinghy in North America and Europe, and QMI is a builder based in Rhode Island, USA.

Each of these Builder Agreements required LPE and QMI to pay royalties to both Kirby and BKI for the right to manufacture (as were all authorised builders), in accordance with the Laser Construction Manual, a ‘Laser’ sailboat. Any failure to pay these royalties represented a condition of default of the relevant Builder Agreement.

Is it a real ‘Laser’ …

In the manufacturing of a ‘Laser’ dinghy, the Laser Construction Manual required that two small plaques (adhesive labels) be affixed to the boat. The first of these plaques was referred to as the “ISAF Plaque”, and the second, the “Builder Plaque”. The Laser Construction Manual dictated the specification and positioning of these plaques.

The authority for ISAF to issue the ISAF Plaque was provided by BKI. The ISAF Plaque was issued directly by ILCA to each ‘Laser’ dinghy built by an authorised builder after assigning each ‘Laser’ a unique sail number. This allocated sail number was specifically noted on the ISAF Plaque, and included the phrase, “Authorised by the International Sailing Federation, the International Laser Class Association, Bruce Kirby Inc. & Trade Mark Owner.” This phrase, in effect, confirms that the host hull was a ‘Laser’ dinghy designed by BKI and that use of the Kirby design has been authorised.

The Builder Plaque was to include the phrase, “Laser Sailboat Designed by Bruce Kirby”. In practice, while the Builder Plaque was made by the builder’s themselves (usually incorporating their own logo), the language was supplied by the Laser Construction Manual.

Generally, these two plaques became the sole means by which any person (sailor, potential customers, racing official etc) could confirm whether what they were looking at was indeed a ‘class legal’ authorised ‘Laser’ dinghy.

So, very simply, without these two plaques positioned as called for by the Laser Construction Manual, no sailboat is a valid class legal ‘Laser’ dinghy.

Time to sell … ‘estate planning’ …

For many years, both LPE and QMI paid Kirby and BKI royalties – no problems.

In 2008, Kirby decided to sell his rights in the ‘Laser’ design to a New Zealand company, Global Sailing Limited (GSL), owned by the Spencer family. Kirby reports in a future article that this initiative was ‘estate planning’ on his part, and that his selection of GSL was in the best interests of the class moving forward in that they had been building ‘Lasers’ through Performance Sailcraft Australasia for many years.

This Sale Agreement would see GSL receive all of Kirby and BKI’s interest in the ‘Laser’ design including certain intellectual property rights, and all rights under agreements entered into between Kirby, BKI and all authorised builders – including LPE and QMI.

Very relevant to this story is that the Sale Agreement did not include registered trade mark rights to the name BRUCE KIRBY, which BKI had registered before the United States Patent & Trademarks Office (USPTO) on 11 November 2008 – ownership of these rights were retained by BKI.

It is also worth returning briefly to my note above concerning the regional or territorial manufacturing strategy of the design to meet global demand.

Ownership of registered trade marks to the LASER word and the ‘starburst’ insignia/logo were held by certain builders for use in marketing the boat in their respective regions. None of Bruce Kirby, BKI, or ILCA owned, and therefore had control over, the registered trade mark rights to the ‘Laser’ brand. As such, these were never intellectual property rights that GSL were able to take control over.

As a consequence of the sale to GSL, all builders were no longer to pay royalties to Bruce Kirby or BKI, but instead to GSL. This appears to have been an undisputed understanding among all actors in this story.

Here we go …

At some stage after the sale to GSL, LPE and QMI appear to have made an affirmative decision to stop paying royalties. And this is where the story really begins.

With two authorised builders taking this action, the value of what GSL purchased then becomes compromised.

Ultimately, there were no registered forms of intellectual property (ie. utility patents, design patents, trade marks) on the ‘Laser’ design or the commercialisation of it – later confirmed by Kirby in various reports. Everything of commercial value appears to have been wrapped up in the Builder Agreements (ie. the royalties from these) and any copyright in the Laser Construction Manual.

Kirby made attempts to stop LPE and QMI to cease building boats brandishing his name (by way of the two plaques) and not paying royalties. In March 2010, Kirby requested that ILCA cease issuing ISAF Plaques to both LPE and QMI. In May 2011, the Builder Agreement with LPE was terminated. Payment of royalties ceased from QMI as of late January 2011.

However, LPE and QMI continued selling Lasers donning the two plaques.

In late 2012, Kirby wrote to both LPE and QMI, again noting very clearly that they were each not entitled to obtain plaques or deal in the design in any manner.

Again, the actions of both LPE and QMI did not change – and both continued manufacturing and selling the dinghy.

Start of trade mark infringement litigation in the US …

In March 2013, Kirby and BKI filed a lawsuit against a number of parties on a number of grounds. Relevant to this discussion, two of those defendants were QMI and LPE and the boats each produced from October 2011 to April 2013.

Key allegations against QMI and LPE concerned registered trade mark infringement under US law (specifically, the Lanham Act) due to the presence of the BRUCE KIRBY trade mark on the plaques, common law misappropriation of the BRUCE KIRBY name, and breaches of the Builder Agreements.

This primary thread of litigation lasted around 7 years (other related episodes of litigation involving various of the parties regarding distinct matters of contention also occurred during this time frame) and concluded on 1 February 2021 in a unanimous jury verdict finding in favour of Kirby.

But more on that later …

ISAF and ILCA’s response to the developing drama … lets change the rules

A requirement in the ‘Laser’ class rules was that any authorised builder needed a building agreement from Kirby or BKI.

In early 2011, its understood that ILCA started discussing strategies for dealing with the developing builder dispute for protecting the future of the class. One such strategy was to change the ‘Laser’ class rules. Specifically, it was proposed to remove Kirby’s name from both the ISAF and Builders Plaques.

These discussions resulted in ILCA reaching out to its membership to vote on a fundamental rule change that would eliminate the then requirement for a builder to have a building agreement in place with Bruce Kirby or BKI. ILCA believed that the proposed change ‘will eliminate uncertainty over ISAF and ILCA approval, give manufacturers continued reasons to support the class and satisfy the demands of current and future class members.’

In September 2011, it was reported that Kirby and GSL reached an agreement that saw Kirby regain ownership of the rights that had been sold to GSL. It appears that this move was with the view to preventing the need for the rule change proposed by ILCA. Kirby was reported as saying:

“I signed the contract this morning. The design rights have reverted to me. I am hoping now that the ILCA will drop the whole idea of a rule change, and I will be taking steps immediately to get the confusion over builders and builders’ plaques straightened away. I have confidence that I will have class and ISAF support with this.

It’s been a long drawn out hassle, but the door is now wide open for the class and builders to come together for the benefit of all concerned, and especially Laser sailors worldwide.”

This proposed class rule change was approved in 2012 – by a reported 89.3% of ILCA members.

However, it is also a ‘Laser’ class rule that any fundamental change of this nature must be approved by ISAF before it comes into effect.

Some ISAF heat …

What I haven’t mentioned yet was that the original lawsuit filed by Kirby and BKI in the US also named ILCA and ISAF as defendants (alongside LPE and QMI). Kirby and BKI alleged that both ILCA and ISAF were assisting LPE by continuing to supply ISAF Plaques.

As noted above, Kirby had tried to stop ILCA from issuing plaques to LPE and QMI – but to no avail. As you can imagine, ILCA was not a party to any of these agreements but were merely proceeding as they have always done, responding to requests from LPE and QMI for plaques as new boats were being built and requiring sail numbers. The contractual mechanisms between the builders, GSL and Kirby/BLI were not within its jurisdiction.

It’s reported that, on 25 March 2013, ISAF formally requested that ILCA cease issuing ISAF Plaques to LPE and QMI:

“The reason for this decision is that ISAF has concluded, based on the correspondence and court papers received from Bruce Kirby’s attorneys, that the Builders are no longer licensed by Bruce Kirby and/or Bruce Kirby Inc. to build the Laser class boat (as required by the 1983 ISAF Agreement and our 1992 Plaque Agreement).”

On 23 April 2013, ISAF approved the proposed rule change enabling its effect, thereby eliminating the requirement for an authorised builder to have a Builder Agreement to build the ‘Laser’ dinghy. While before this date Kirby’s name appeared on the two plaques affixed to each boat made/sold by LPE and QMI, this was not the case afterwards.

So, this rule change removes Kirby and BKI’s role from the supply equation.

This, it seems to me, was the more immediate problem if the ‘Laser’ class was to be maintained as Olympic equipment – specifically in terms of certainty of supply of that equipment (for men and women) for ISAF events and, more importantly, the approaching Olympic event in 2016. I’m unable to confirm, but I understand that supply contracts for the 2016 event was approved by ISAF in 2012 – possibly shortly after the ILCA membership approved the proposed rule change.

But this rule change didn’t address the commercial issue created as a consequence of regional builders having acquired territorial ownership of the trade mark rights to the ‘Laser’ brand, ie. the risk that any owner of the ‘Laser’ trade mark rights could exercise their right to prevent anyone trying to supply ‘Laser’ branded equipment in its trade mark territories.

Trade mark infringement lawsuit in Europe …

It seems that it wasn’t long before that risk would be realised and tested.

In a decision of Antwerp’s Commercial Court in September 2013, Velum Limited (Velum) succeeded in bringing legal action against BVBA OPITEAM (OptiTeam) for registered trade mark infringement. This chapter of litigation appears to go back to May 2012.

Velum is the owner of the Benelux trade marks to the LASER word mark, and the LASER logo. Velum contended that OptiTeam used the marks without its approval to sell equipment sourced from Performance Sailcraft Australia – an authorised builder of the ‘Laser’ dinghy based in Australia.

While OptiTeam made some attempt to invalidate the trade marks, as every defendant in these types of litigations is entitled to do, each was dismissed by the Antwerp Commercial Court fairly quickly.

Specifically, OptiTeam tried to argue that both trade marks were not sufficiently distinctive to have been granted registration. For those unaware, a requirement for trade mark registration is that the trade mark is distinctive, as compared to be being descriptive of the goods/services that the mark is to be registered in relation to. On this ground, the Antwerp Commercial Court was unpersuaded by OptiTeam’s arguments. A good degree of thanks must surely go to Doug Balfour for his brilliant selection of what was held to be a distinctiveness name/brand.

OptiTeam then argued that the trade marks were now generic, and no longer had the ability to ‘evoke a direct association with the commercial origin’. In my view, this was the more credible line of attack for OptiTeam. A registered trade mark can be vulnerable to this attack, and cancelled, if it has been allowed to become a generic term (eg. a noun) for the good or service that it was originally registered in relation to (in a distinctive capacity).

In effect, OptiTeam were trying to argue that there was now no distinction between the laser, as a brand name, and the dinghy of the ‘Laser’ design. The Antwerp Commercial Court was again unpersuaded by OptiTeam’s attack on this ground.

Ultimately, the Antwerp Commercial Court found that Velum’s trade mark rights were valid and had been infringed by OptiTeam.

This outcome was affirmed by the Antwerp Court of Appeal on 19 January 2015, in an attempt by OptiTeam to appeal the initial decision.

Brief commentary

In my view, this result is a direct consequence of whatever legacy decision led to the assignment of territorial ownership of the LASER trade mark rights to the succeeding builders of the time.

In the early stages of any new venture or business collaboration, everything is fine when all commercial interests are aligned. However, business is business, and any well founded initial alliance can disassemble very quickly when a diverging commercial interest arises that concerns one of the parties.

But there is a lesson here. Generally, ownership of intellectual property rights equates to a greater scope of available options to the rights holder for any commercial circumstance.

If you want to learn more about registered trade mark rights in Australia or abroad, please contact us.

Rebranding exercise … the ILCA dinghy, European anti-trust regulations …

In early 2019, ILCA announced that from 25 April 2019, all new class-approved boats will be sold under the “ILCA Dinghy” name.

The rebranding exercise that ILCA has now taken on is, I think, the only plausible move that it had available to it in safeguarding the future of the class. While I think that it’s sad that Doug Balfour’s founding brand name will evaporate in time, the acronym “ILCA” does seem to make sense. Provided that all operable intellectual property rights remain with the class association, the constraints of recent history should be severed.

It is pleasing to see that the word mark ILCA is registered in a number of jurisdictions with common ownership (the Laser Class Association Inc).

This branding strategy was to avoid the trade mark issues we have discussed, but also to comply with certain requirements of European competition law.

From late 2018, a number of equipment manufacturers in Europe initiated anti-monopoly actions against World Sailing (the rebranded ISAF) claiming that they were being denied access to the Olympic sailing equipment market. Because of the size of the market and the tight control for new manufacturers, the European Anti-Trust Commission made the ‘Laser’ class a central focus of its investigations.

As a result of this scrutiny, World Sailing implemented an anti-trust review policy under which all Olympic classes were evaluated for compliance with relevant anti-trust regulations. The ‘Laser’ class was the first Olympic class to go through this process. Following the review, World Sailing, in May 2019, voted to retain the ‘Laser’ class standard and radial rig equipment for the 2024 Olympic Games, subject to the requirement that ILCA demonstrate compliance with World Sailing’s ‘Olympic Equipment Policy’, requiring open builder and equipment supplier access.

I note that a number of changes to the ‘Laser’ class rules have occurred in recent years. Without diving into each of them, I understand that some of these changes have largely been seeking to ensure relevance with the modern operating environment, in terms of certainty in supply of class legal equipment and contractual compliance.

Returning to the US litigation matter …

OK, let’s return to the lawsuit that Kirby and BKI filed against LPE and QMI in the US.

Ultimately, the case went to jury trial and a unanimous verdict returned on 1 February 2021:

- QMI were found to have willfully committed trade mark infringement and willful false designation of origin.

- Both QMI and LPE were liable for common law misappropriation of Kirby’s name.

The Lanham (Trademark) Act is the primary federal trade mark statue of law in the United States. In short, a trade mark registrant has a legally protected interest in its mark conferred by the Lanham Act protecting against use of similar marks if such use is likely to result in consumer confusion.

There was no dispute that BKI was the trade mark registrant of the BRUCE KIRBY mark. Ownership of the BRUCE KIRBY mark was held by BKI and had not transferred to GSL as part of the sale in 2008 (as had been contended otherwise). Had BKI been found to not own the KIRBY mark, then BKI would not have been able to bring the claim against QMI.

As to consumer confusion, the plaques had become the go-to visual indication for assessing class compliance to a potential customer. As these were being applied by QMI, the jury held that the Builder Plaque featuring the BRUCE KIRBY trade mark implied to potential customers that the boat was approved by BKI.

Accordingly, the jury found that QMI did use the BRUCE KIRBY trade mark without BKI’s consent and infringed BKI’s rights under the Lanham Act.

The basis of Kirby’s allegation against QMI and LPE as to misappropriation of his name was its wrongful use. In the US, it is well established under common law that a person has a protected interest in the exclusive use of their own identity, insofar as it is represented by their name or likeness. It is therefore against the relevant law to use someone’s name or likeness to advertise a business or product without the person’s consent.

In short, the jury found that it was an invasion of Kirby’s privacy for LPE and QMI to use Kirby’s name (on the plaques) for commercial advantage (selling ‘Laser’ dinghies) without his consent.

Ultimately, and concluding this episode of litigation, a damages award of USD 2,056,736.33 against QMI, and a compensatory damages award of USD 2,520,578.81 was made against LPE.

I note that Bruce Kirby, at the age of 92, passed away on 18 July 2021, not long after this verdict was handed down.

Lessons …

With the view to extracting some learnings from the above history, I think the following points are useful:

- Registered trade mark rights are extremely useful in protecting one’s brand. Unlike patent and registered design rights, registered trade mark protection can be maintained perpetually provided renewal fees are timely paid.

For the present case outlined here, it was entirely the correct decision to secure registered trade mark rights for the LASER mark and the starburst logo, both in the US and abroad. - For a trade mark to qualify for registration, one key criteria is that it must be distinctive of the goods or services to which it is to be registered in relation to. In effect, the more distinctive the trade mark is, the more effective it will serve as a trade mark, and the more straight forward it should be to secure rights for.

For the present case, Doug Balfour did an excellent job in selecting the name for the class, and this was very clearly validated during litigation before the Antwerp Commercial Court, and again when the case came before the Antwerp Court of Appeal. - An advantage with registered trade mark protection is that rights can be sought on a region-by-region basis. This means that a trade mark registrant can select where they want to secure trade mark rights.

It was again the correct decision to secure registered trade mark rights for the ‘Laser’ brand in foreign regions given (at least) the international appeal of the design. We would ordinarily recommend that registered trade marks are sought in all territories where one is considering operating commercially.

In my experience, anything other than individual ownership of a family of one or more IP rights has the potential to become problematic when the commercial environment changes. Unless circumstances dictate (very) strongly otherwise, we would always ordinarily favour sole ownership of IP rights. In cases where this cannot be possible (for whatever reasons), we strongly recommend an agreement being prepared that defines, as comprehensively as possible, the commercial relationship between the owners of IP rights.

In the present case, in the early 80’s, each of the licensed builders were allowed to acquire ownership of the LASER trade mark in its territory. As has been shown, this approach became problematic when the parties fell out. Had, Kirby or BKI owned all of the trade mark rights (US and foreign) to the ‘Laser’ brand, there would have been more effective options available to exercise for dealing with LPE and QMI which could have brought an earlier resolution to the matter and/or prevented the need for the US and European litigations.

If you want to learn more about registered trade marks or have any questions regarding any of the above, please contact us.